And since you know you cannot see yourself, so well as by reflection, I, your glass, will modestly discover to you yourself, that of yourself which you yet know not of.

William Shakespeare – Julius Caesar, Act 1 Scene 2

In this scene from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, Cassius suggests to Brutus that he knows things about him that he himself cannot yet see. Brutus is obviously aware of many aspects of his ‘self’ though his own reflection, but there remain aspects to which he is blind. The glass Cassius speaks of is perhaps akin to that which we might find in an interrogation room – in that, when viewed from the inside, a mirror, and from the outside, a window. Whilst Brutus sees himself in the mirror, Cassius, viewing in, is afforded a window that reveals more than mere reflection – both positions offer aspects of knowing Brutus’s ‘self’.

As Brutus stares into his reflection in the mirror, his own presence obscures his view back in. Cassius, looking in through the opposite side can see both Brutus himself as well as aspects that fall within Brutus’s shadow. Dialogue based upon such observations by Cassius may allow Brutus additional insight into his ‘self’. Of course, Brutus does have a degree of control as to what Cassius can see, perhaps situating things in specific places, or purposefully hiding other things from view. As the relationship and trust between them develops, Brutus may choose to disclose to Cassius some of these things concerning himself (his ‘self’).

Shakespeare aside, we each have a pane of glass that acts as both a mirror and a window. As we look into the mirror, we construct a picture of our ‘self’; as others look in from the other side, they may see aspects to which we are unaware. Considering both points of view – that in the mirror and that through the window – can afford us heightened self-awareness.

The new Queensland Music Extension syllabus[i] is founded upon students’ exploration of metacognition and self-systems through the key ideas of locating best practice, engaging in an apprenticeship, and reflective practice. These are a demanding set of ideas to explore, and genuine and sincere reflection upon them as we work towards greater self-awareness is a very challenging exercise, and one that requires explicit teaching, scaffolding and practice. Becoming self-aware is a key element of reflective practice. Understanding our own processes and how these influence the way in which we approach our practice can assist us to function more efficiently and effectively as we move towards our own model of best practice.

I have found that engaging with several reflective models in class a good way to guide and structure students’ thinking and reflection as they engage in bettering their creative practice and heightening their self-awareness. We investigate the 5Rs Model of Reflective Practice[ii], the Gibbs Reflective Cycle[iii], Kolb’s Learning Cycle[iv], John’s Structured Model of Reflection[v], Jay and Johnsons Typology of Reflective Practice[vi], the Driscoll Reflective Model[vii], Schön’s Reflective Model[viii], and the Atkins and Murphy Model[ix] to give structure and make meaning of what we see when we look into our metaphorical mirrors. We work descriptively, comparatively and critically with these models, looking for connections and similarities, and ultimately ones that resonate with us personally as practitioners. But what might others see as they look in through our window?

Last year, a student who was preparing for her performance asked me what she didn’t know about herself. She was a reflective and self-aware student; however, she wanted to know about the aspects of her musical self that she was blind to – potentially what others saw as they viewed her practice through her window. This prompted a memory of a model I had studied in an educational psychology unit at university – the Johari Window[x]. The Johari Window is essentially a tool to look in one oneself to heighten self-awareness, involving both self-reflection and engagement in a dialogue of disclosure with and solicitation of observational information from others. Viewed through the lens of developing technical, expressive and psychological aspects of one’s musical performance, the Johari Window has much to offer us as we aim for our own models of best practice.

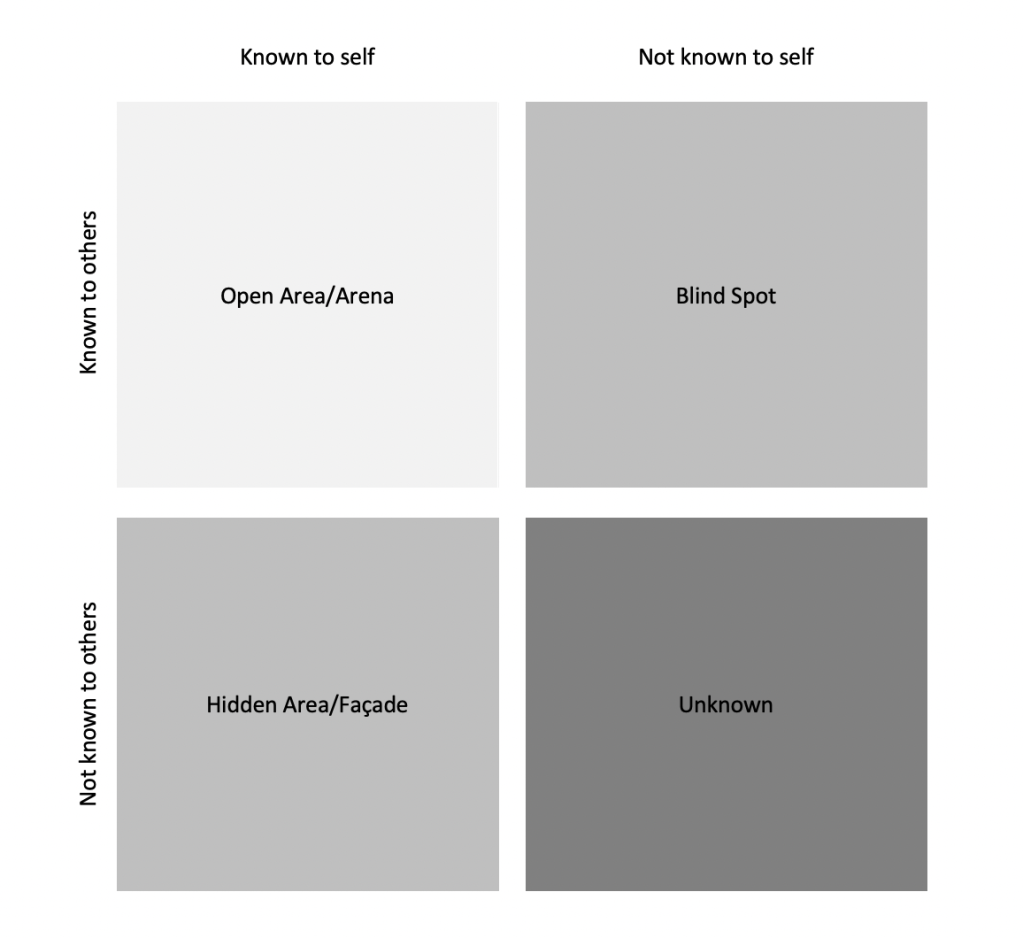

The idea behind the Johari Window is relatively simple; there are things about us that are known by both ourselves and others, things that we only know ourselves, and things that others know about us that we are unaware of, just as with Cassius and Brutus. These three panes of the window are our open area, our hidden area, and our blind spot respectively. The fourth pane comprises areas of our functioning that have not yet been elicited through experience or reflection. These four panes form the Johari Window:

In the context of musical performance (including the technical, expressive, psychological, and as a subset of the Johari Window’s full application), the open area (or arena) represents things known about your practice to yourself as well as to others. The hidden area (or façade) represents aspects of your practice known to you, but not to others. Your blind spot is known to others, but you are unaware of these aspects of your practice. The unknown area represents those elements of your functioning that are unknown both to yourself and to others.

In using the Johari Window as a supportive mechanism, students are encouraged to expand their open area (arena) in pursuit of heightened self-awareness. They can do this through the solicitation of feedback from others, thereby reducing their blind spot – this is largely in dialogue with teachers, tutors, peers with whom they engage in an apprenticeship. Often this reflection, supported by the relationship and care of the apprenticeships entered into, encourages a degree of self-disclosure, and often this is psychological in nature – fears of comparison, incompetence and unworthiness often arise in discussion. Engaging in dialogue here can be rich as aspects of the hidden area (façade) are revealed. This can be terribly confronting, but the students are aware that they are the ones in control of their own hidden arena (façade). They can choose to open these up in their own explorations and in confidence – placing them in their open area (arena) – or they can reflect on these personally and privately in their hidden area.

It is through careful discussion here that – in both the solicitation and disclosure of information – students can critique their own action and engage in metacognitive strategies, as they consider, come to know and understand their own model of best practice. Considering the view both in and through the glass (our mirror and our window), is perhaps the only way we might begin to see the unknown aspects of the person (as performer) in question.

The Johari Window model is forming a significant part of our initial reflective activity in Music Extension, and when used in conjunction with our more descriptive and critical reflective models, places a ‘multi-lensed’ view on the student – that of their own reflection in the glass, and our (and others’) view back in through the window – in terms of their practice. It has been an effective tool for the generation of discussion about shared concerns and problems, and has afforded a degree of social cohesion and connectedness amongst the class. There is power in this as we cannot see ourselves, to quote the epigraph, “so well as by reflection”, and engagement with this model allows insight into aspects of ourselves “that of yourself which you yet know not of”.[xi]

—–

[ii] Bain, J.D., Ballantyne, R., Mills, C. & Lester, N.C. (2002). Reflecting on practice: Student teachers’ perspectives, Post Pressed: Flaxton, Queensland.

[iii] Gibbs, G. (1988). Learning by doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods. Further Education Unit. Oxford Polytechnic: Oxford.

[iv] Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

[v] Johns, C. (1995). Framing learning through reflection within Carper’s fundamental ways of knowing in nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 22(2), 226-234.

[vi] Jay, J. K. & Johnson, K. L. (2002). Capturing complexity: a typology of reflective practice for teacher education.Teaching and Teacher Education, 18, 73–85.

[vii] Driscoll, J. (1996). Reflection and the management of community nursing practice. British Journal of Community Health Nursing, 1(2), 92-96.

[viii] Schon, D. (1991). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing Ltd.

[ix] Atkins, S. and Murphy, K. (1994). Reflective practice. Nursing Standard, 8(39) 49-56.

[x] Luft, J. & Ingham, H. (1955). The Johari Window, a graphic model of interpersonal awareness. Proceedings of the Western Training Laboratory in Group Development. Los Angeles: California.

[xi] Extract from Julius Caesar: http://shakespeare.mit.edu/julius_caesar/julius_caesar.1.2.html