With the new academic year comes renewed thinking and reflection on my practice; how my ideas and actions are embraced by my philosophies and ideals, and how I might seek to challenge my current ‘ways’ in considering new contexts and the influence of others. Such reflection has long characterised my approach to teaching and learning; I have always seen this as an extension of my professionalism, not an addition to it. For me, this viewpoint ensures that I am endeavouring to provide the most effective and impactful practice.

In one of our main professional learning sessions at the start of the school year we were challenged to think about this very position – the efficacy and impact of our practice. We were encouraged to be ‘curious and courageous’ about our own pedagogical decisions and actions; challenged to consider our own continued investment into this through ongoing reflection, engagement with research, and our willingness to implement new ideas and perspectives. Refreshingly, this allowed for a personalised and targeted examination of aspects of our work that we might feel beneficial. These two words simple words, if held up against our current work, invited reflexive thinking and critical evaluation.

As the ways in which students (can) engage with and in music has changed so significantly across the span of my career, the ‘curious and courageous’ message was both affirming and ‘positively confronting’. The need to be flexible, agile, and responsive to changing contexts and conditions is important. When it comes to teaching and learning in music, the way in which we approach what it is we teach and how we teach it must be constantly negotiated and remain malleable. We may discard ideas and approaches, reposition or reappropriate them… what is ‘courageous’ one year, may be ‘pedestrian’ the next, and our continuing curiosity maintains the currency of our courageousness.

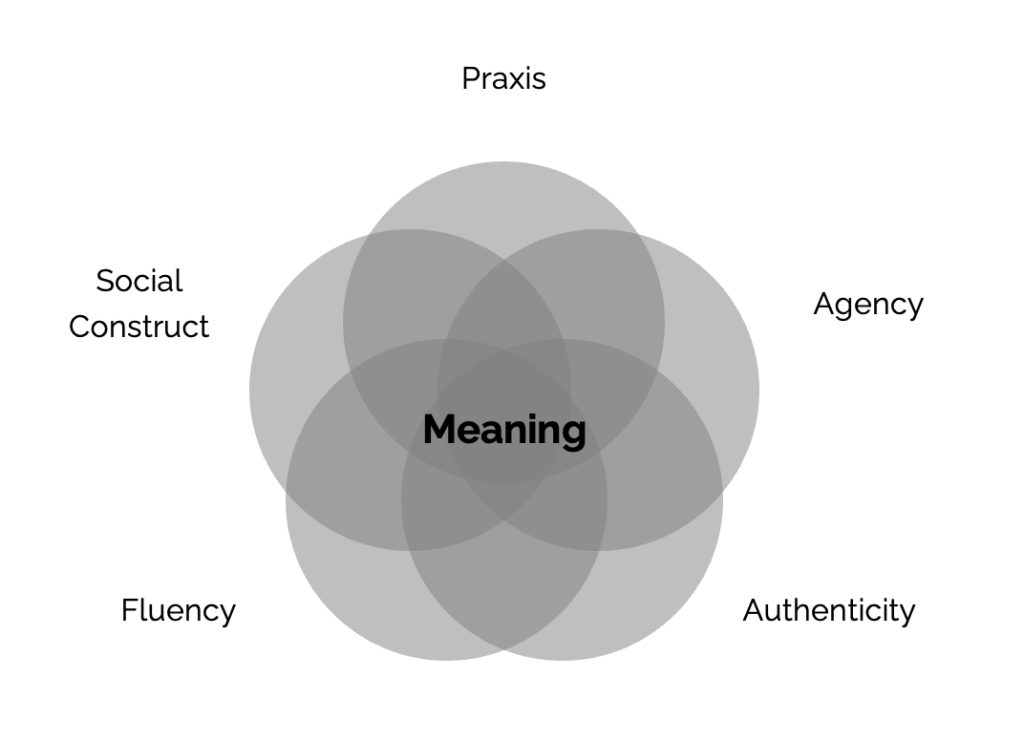

This curiosity to action ‘better’ practice was fundamental to my doctoral journey – in this, I sought to become more aware of the conditions in which my pedagogical approaches were positioned and how they assisted students make meaning. Though I found an ‘answer’ to this question, it was certainly not definitive in the sense that my practice was then ‘future-proofed’. The initial study located five conditions for the provision of meaningful[i] music education – that of praxis, student agency, authenticity in working in and with music, fluency with music as a discourse, and the social construct surrounding music learning – which ultimately formed ‘spaces’ where pedagogy might be best positioned for this to occur.

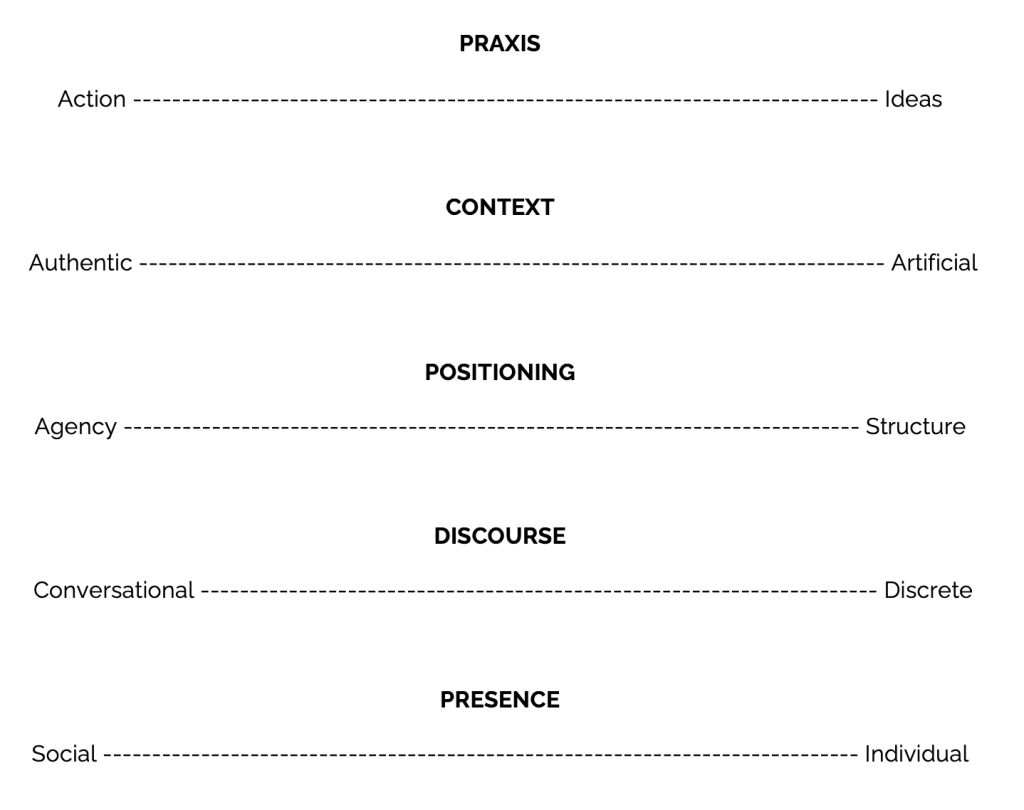

As mentioned, the limitations of this model became apparent through continued practice, with the conditions proposed not fully embracing the complexities of the classroom. Curious to see a model more reflective of and embracing the realities I was facing in the classroom; I sought to reframe and rearticulate these conditions through ongoing critical reflection upon its application. The findings of this current phrase of investigation position five ideals – praxis, context, positioning, discourse and presence. Rather than ‘spaces’ for pedagogy to consider (as shown in the initial model), this revised model presents independent yet interrelated continua in which practice can be situated. Some of the initial conditions remain; others have been more clearly defined – collectively, the conditions now have ends to their continua.

For now, I consider meaningful practice as responsive to the dialectic tension between these ideals; they remain fluid in and between musical encounters as the nature of learning is influenced and informed by the actions of both teacher and student. Upon these continua, dualistic notions of action and ideas in relation to praxis, authentic and artificial contexts for learning, the degree of agency or structure with regard to the positioning of the learning, the nature of discourse as conversational or discrete, and the social versus the individual presence of the learner, are positioned. I’ll do my best to summarise each below.

When we consider praxis, we are deciding where ‘good places’ to explore both the action of making music and the action within working with music ideas in the mind. This challenges the idea that praxis is a purely practical pursuit, or that it sits opposed to theory; more accurately, it suggests that we work with – not exclusively work on – music ideas and actions. This is both a physical and cognitive engagement – traversing between actions and ideas – and does seem to offer a more comprehensive and contextually clear frame for working with music.

By nature of its positioning and the nature of learning, pedagogies often deal in artificial, procedural, and knowledge-based realms; though, we endeavour for authenticity of experience wherever possible – both have merit and value in the construction of meaning in the school context. We need to be careful, however, when dealing with authenticity, that we don’t render the familiar strange. At the very least, we should be aiming for procedurally authentic ways of learning about and in music, irrespective of context.

Tied to praxis and context, pedagogies must support music learning through structure, routine and repetition, as well as offering agency, experimentation and exploration. Both work in dialectic tension – as supportive ends pulling together threads of understanding. Working at the extremes of the agency and structure continuum for extended periods are not good places to go; endless freedom can stifle just as much as structure; both are needed, but as fluency with music discourse becomes more complex, we should shift towards greater student agency.

The discourses our pedagogy supports and provokes must, as far as possible, mimic language acquisition. It is the discrete, disconnected, isolated language units that we invest in that form a basis for increasing levels of conversational fluency and general musical discourse. Pedagogies should enable increasingly complex conversations to occur; discrete units offer the data, understanding and wisdom allow us to converse.

Our pedagogies must also consider the way we learn individually and collectively. Whilst much music learning is engaged in social groups, especially in the school context, much of it is also not. Much musical activity is engaged with socially, for examples in musical groups, and there are many practices in which music is engaged with at an individual level, such as in much composition activity. There are further distinctions to be made between modes of musical engagement, style and genre, and personal pathways forged by the student.

These are an extremely interrelated set of continua that contain many complexities, yet they provoke in me a sense of curiousness as to how my pedagogies may be best positioned for meaningful learning. The framing of each ideal is relatively fixed (for now), but the way I (could) work within each remains flexible and accommodating of challenges and new pedagogical approaches.

This line of thinking is one part of a continuous journey of critical reflection on my own action and on theory as applied to music education. The continuation of the questioning underpinning my doctoral project sees the extended implementation of action research and practice-based inquiry models to further inform my practice and my critical and reflective thought. Of course, there is merit in this enterprise, as education contexts and systems undergo constant change from both internal and external pressures, and my own context is far from immune from this.

The use of this new pedagogical frame will see the continual generation of new and situated knowledge, and provide a response to the claimed paucity of critically reflective teacher-based research. I continue to posit teacher-based research as a model for powerful social and educational change, and that all good teachers are researchers. Critical reflection and inquiry are inseparable from good practice, and teachers best know their own contexts. Action and practice-based research is powerfully educative and has a role in the betterment of both teaching and learning in music education. I strongly encourage other teachers to engage in research into their own classroom contexts, as this will provide a platform for the sharing of knowledge and inform our collective understandings. It is hoped that voicing this thinking may act as a precursor for other teachers who wish to find answers to their own classroom issues. This study provides an adaptive not adoptive model in such explorations, and further research building from this study will serve to better music education practice as a whole.

So, this is one way in which I am continuing my curiosity of my practice this year. Perhaps this thinking might be of value to you and your practice? Please let me know if it provokes any of your own thinking and change in action, and feel free to add your own thoughts.

[i] The use of the term ‘meaningful’ referred to a ‘transaction’ attentive to working with music musically – something of value and currency in its use and application, and one that can allow us to learn of the essential components of music and to then ‘converse’ using them.