What follows are some brief reflections on ‘cognitive load theory’ and learning more generally. I am really interested in others’ viewpoints on how CLT ‘fits’ within music education. Hopefully, this generates some discussion…

What is learning?

As we explore our individual responses to this question there are sure to be common threads that emerge. For me, meaningful learning comprises change, often impelled by a degree of cognitive dissonance. I have long maintained that you learn when you don’t know how to respond, but that in this mental working space the dissonance placed before us and the cognitive expenditure required to minimise this, need to be relative. Finally, learning should have a degree of permanence and transferability to new contexts.

If we take this as a working definition, then how do we best negotiate learning? How do we help students learn? These questions invite further exploration into the ‘architecture’[i] of learning – what it is and how it occurs.

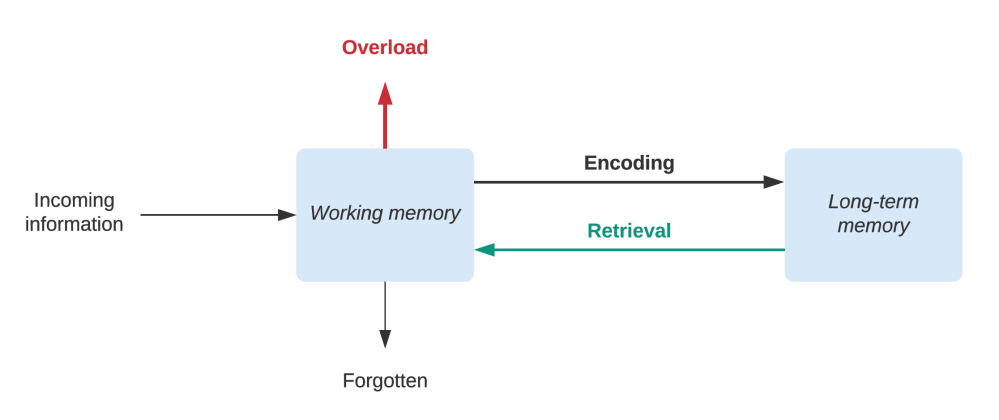

We are continuously bombarded with sensory information; our sensory memory filters out a great deal of this but keeps an impression of the most important items long enough for them to pass into working memory. It is the job of our working memory to then process or discard this information – to ascertain what is useful taking forward. As we consider the questions above, we will find it significant that the working memory of young adults is limited to working with three to five meaningful items at any one time.[ii] Information that is deemed useful is then encoded into long-term memory, where it is categorised in knowledge structures called schemas.[iii]

I have been doing a great deal of reading on the nature of learning as I’ve questioned my own practice, and a theory that embraces the cognitive ‘architecture’ detailed above is that of cognitive load theory (CLT). CLT positions learning as a change to long-term memory. It was first proposed in the late 1980s by educational psychologist, John Sweller, now Emeritus Professor at the UNSW Sydney, and his work is a seminal piece of research[iv] that underpins a significant body of thinking in education.

CLT is founded on the idea that, as our working memory has a limited capacity, our pedagogical considerations should avoid overloading it with information. If the cognitive load exceeds processing capacity, then learners will become overwhelmed and not retain information. As our long-term memory is essentially infinite, learning occurs when information is encoded to and retrieved from schemas in our long-term memory. Information retrieved and utilised from long-term memory lessens the demand on our working memory, allowing it to process new information more effectively. With extensive practice, information can be automatically recalled from long-term memory with minimal conscious effort, further reducing the burden on working memory. This may be summarised diagrammatically as:

Adapted from Atkinson and Shiffrin (1968) and CESE (2018)

A simplified analogy could be that of our memory as our desk. If the desktop is cluttered with many disparate items, then we may find it hard to locate and use what we need. If these items were to be housed in meaningful collections in specific drawers, we would be able to access and use them quickly and with relative ease, without unnecessary cognitive expenditure. We would then bring these to our clean desktop, now uncluttered with extraneous items, and have a clean space to work.

Unashamedly, CLT provides theoretical and empirical support for explicit models of instruction that are accompanied by sustained practice and regular feedback.[v] I argue that this should be a foundation for any pedagogical approach – we cannot be dismissive of the fundamental value of these processes in the ‘architecture’ of learning. They give rise to more complex processes, the utilisation of knowledges that we have compiled in our own schemas, which can be applied to new contexts and new problems. You may also recognise knowledge utilisation as top tier of the taxonomy that underpins the new Queensland syllabuses.[vi]

To this end, I do not find CLT at all problematic to constructivist, inquiry or problem-based approaches to learning, it sits as foundational to these – it is fundamental to all learning. Through genuine inquiry-based and project-based approaches, we provide guidance and structure, but we need to be mindful of the schemas students have access to and the cognitive demand that is placed upon them. When instructional guidance is minimal, and knowledge structures (schemas) do not exist, students can become overwhelmed. Now, guidance can be minimal, but there needs to be a foundation of understanding of the subject matter and the cognitive processes that are applied to it. We release responsibility to the student when these knowledge structures are in place. Arguments against this perhaps conflate theory of learning with theory of instruction, they are distinct entities.

The CLT literature identifies seven strategies that can assist teachers support student learning.[vii] These strategies are clearly synthesised in an excellent publication by the Centre for Education Statistics and Evaluation (CESE),[viii] which is perhaps the most accessible overview of CLT I have read. I present these here in summary and encourage you to read this publication to further inform you own practice. These strategies are also placed within a series of useful questions for our consideration.

The strategies are:

- tailoring lessons according to students’ existing knowledge and skill

- using worked examples to teach students new content or skills

- gradually increasing independent problem-solving as students become more proficient

- eliminating inessential information

- presenting all essential information together

- simplifying complex information by presenting it both orally/aurally and visually

- encouraging students to visualise concepts and procedures that they have learnt.

Perhaps they are central to your practice already? These may seem simple, but if you’re anything like me, they are challenging to genuinely achieve. The CESE publication provides some additional detail as to the effectiveness of the strategy in relation to learning as well as several examples from a range of curriculum areas.

The strategies summarised here encourage us to consider the cognitive load we place upon our students in their learning. If we plan to optimise the working memory of our students, then we maximise the construction of their schemes of meaning, which can be retrieved and utilised to frame new learnings. No matter our pedagogical approach, these are fundamental considerations. Being aware of the ‘architecture’ of learning and designing our pedagogies around this, is only of benefit to our students. There are wide reaching gains to be made here.

_______

[i] I have borrowed this term from Kirschner, Sweller and Clark (2006) as referenced vii below.

[ii] Cowan, N. (2010). The magical mystery four: How is working memory capacity limited, and why? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19(1), 51-57.

[iii] Atkinson, R. C. & Shiffrin, R.M. (1968). ‘Human memory: A Proposed System and its Control Processes’. In Spence, K.W. and Spence, J.T. The Psychology of Learning and Motivation (vol 2). New York: Academic Press.

[iv] Sweller, J. (1998). Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cognitive Science, (12), 257–285.

[v] Centre for Education Statistics and Evaluation (2018). Cognitive load theory in practice: Examples for the classroom. CESE: Sydney. Retrieved May 13, 2020 from https://www.cese.nsw.gov.au//images/stories/PDF/Cognitive_load_theory_practice_guide_AA.pdf.

[vi] Marzano, R. J. & Kendall, S. (2007). The new taxonomy of educational objectives. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

[vii] As a start, I would recommend: Sweller, J. (1998). Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cognitive Science (12), pp. 257 285; Kirschner, P. A., Sweller, J. & Clark, R. E. (2006). Why minimal guidance during instruction does not work: An analysis of the failure of constructivist, discovery, problem-based, experiential, and inquiry-based teaching, Educational Psychologist, 41:2, pp. 75-88; and also, Reif, F. (2010). Applying Cognitive Science to Education. Thinking and Learning in Scientific and Other Complex Domains. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

[viii] Centre for Education Statistics and Evaluation (2018). Cognitive load theory in practice: Examples for the classroom. CESE: Sydney.

This is very interesting. CLT certainly underpins much of what I attempt to do, however I’m constantly evaluating if what I’m producing and delivering to students is effective and adjusting accordingly. CLT is certainly something I’m considering in relation to the external exam and how I effectively prepare students given they are listening, analysing and synthesising (unseen/unheard examples) under stress within a short time frame.

LikeLike